Efficient global optimization of multivariate functions with unknown Hölder constants via -dense curves

Abstract.

In this paper, we consider the global optimization problem of non-smooth functions over an -dimensional box, satisfying the Hölder condition. We focus our study on the case when the Hölder constant is not a priori known. We develop and analyze two algorithms. The first one is an extension version of the Piyavskii’s method that adaptively construct a linear secants of the Hölder support functions, avoiding the need for a known Hölder constant. The second algorithm employs a reducing transformation approach which consists of generating, in the feasible box, an -dense curves, effectively converting the multivariate initial problem to a problem of a single variable. We prove the convergence of both algorithms. Their practical efficiency is evaluated through numerical experiments on some test functions and comparison with existing techniques.

Key words and phrases:

Global optimization, Hölder condition, covering methods, Piyavskii’s method, reducing transformation, -dense curves.2005 Mathematics Subject Classification:

90C26, 65K051. Introduction

Let us consider the following box constrained global optimization problem of finding at least one point and the corresponding optimal value such that:

| (1) |

where the objective function is non-smooth non convex. It is assumed to satisfy the Hölder condition on the -dimensional compact box :

Specifically, there exist a Hölder constant and a Hölder exponent such that:

| (2) |

Here, denotes the Euclidean norm. A primary focus of this work is when the Hölder constant is not known a priori.

Many real-world optimization problems are complex, involve minimizing continuous functions of variables possessing multiple extrema over the feasible domain. Frequently, derivative information is either unavailable or its computation is expensive, rendering standard non-linear programming methods ineffective for finding global optima, as they typically converge only to local minima. Global optimization has thus become an active field of research [11]. The challenges are often amplified by local irregularities (non-smoothness) and the potential existence of numerous local minima within the feasible set. Deterministic global optimization strategies, particularly covering methods, offer a rigorous approach to tackle such problems [11, 19]. The first work on covering methods for univariate Lipschitz functions (the case in (2)) was performed by Piyavskii [13], Evtushenko [6], and Shubert [17]. The widely discussed Piyavskii-Shubert algorithm guarantees convergence to the global minimum by constructing a sequence of improving piecewise lower-bounding functions (sub-estimators) based on the known Lipschitz constant [11]. More recently, research has addressed the optimization of less regular functions satisfying the Hölder condition with [7, 12]. Gourdin et al. were among the first to study the global optimization of both univariate and multivariate Hölder functions using such deterministic approaches [7, 10].

The aim of this paper is twofold. First, we develop a novel technique for univariate Hölder optimization (), extending the ideas of Piyavskii. This method utilizes the secants linked to the Hölder support functions between evaluated points. We address both the case where the Hölder constant is known and significantly, the case where the constant is unknown. For the latter, we propose an adaptive estimation scheme for , which is crucial for practical application and performance. Second, we address the multivariate case (). Direct generalization of Piyavskii’s algorithm to higher dimensions is computationally challenging, primarily because finding the minimum of the multivariate sub-estimator involves determining intersections of complex hypersurfaces [7, 20]. To overcome this, we propose an approach based on dimension reduction. This method transforms the original -dimensional problem (1) into a one-dimensional Hölder optimization problems by exploring the box along an -dense curve [22, 23, 24]. The univariate algorithm developed in the first part can then be effectively applied to these simpler problems.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the univariate algorithm based on Hölder support functions and secant information. Section 3 describes the reducing transformation method for the multivariate case, detailing the use of a specific -dense curve. Section 4 provides numerical results from experiments on test functions and compares the performance with existing methods. Section 5 concludes the work.

2. Univariate Hölder global optimization

Let us begin by considering the problem (1), (2) for a function with a single variable, i.e.,

| (3) |

where the objective function satisfying the following Hölder condition

| (4) |

with a constant and . Let be the desired accuracy with which the global minimum to be searched.

2.1. Sub-estimator function

When minimizing a non-convex function over a feasible set, the general principle behind most deterministic global optimization methods is to relax the original non-convex problem in order to make the relaxed problem convex by utilizing a sub-estimator of the objective function . The Hölder condition (4) allows one to construct such a lower bound for over an interval . From (4) we have

Let and be two distinct points in [a,b], typically with . We define the following functions:

By construction setting or in the Hölder inequality, these functions are lower bounds for on their respective domains of definition within :

The functions and are thus sub-estimators of . Over any sub-interval , both functions are well-defined lower bounds. We can then define a tighter sub-estimator on this sub-interval:

This function is convex (as the maximum of two concave functions, assuming ) and non-differentiable (typically at the point where ). It also satisfies:

| (5) |

The global minimum of over occurs at the point where and intersect (assuming such an intersection exists within the interval). This point is given by:

Thus, in each iteration of Piyavskii’s algorithm, we must solve the following non-linear equation to find this intersection point:

| (6) |

Determining the unique solution to equation (6) within is generally straightforward only for specific values of . For instance, Gourdin et al. [7] provide analytical expressions for this solution when , assuming is known a priori. However, when is large or not an integer, solving equation (6) can be as complex as a general non-linear local optimization problem. To overcome this difficulty, we propose a new procedure below.

2.2. Procedure approach to the intersection point

Let be the same midpoint of the intervals and so

| (7) |

As and are monotone continuous functions on the interval then they are bijective functions. Let and be the inverse functions respectively of and . We denote by and . According to the definition of and we have:

| (8) |

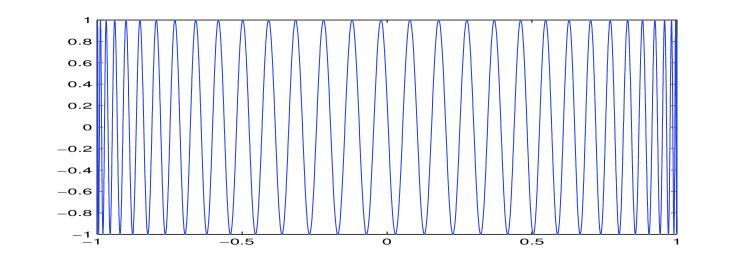

Let and be the two straight secants linked to the parables and on the interval and joining respectively the points , and , , we get

The intersection point of the two secants and is the point the approximate point of the two parables and (see Fig. 1).

Then

| (9) |

Remark 1.

If , the approximate point is immediately the midpoint of the interval . In this case, one can choose:

| (10) |

Proposition 2.

Let be a real univariate Hölder function with the constant and defined on the interval . Let the value (as a constant lower bound of on ). Then we have:

| (11) |

Proof.

The value is given by replacing the variable in the two functions and by the expression of . Since we have defined the function

as a sub-estimator function of over the interval . Then,

The function is strictly decreasing and is strictly increasing over the interval Thus, it follows

In particular, for it then follows:

∎

| (12) |

| (13) |

2.3. Convergence Result of MPSA

Theorem 3.

Let be a real function defined on a closed interval , satisfying (4) with and . Let be a global minimizer of over . Then the sequence generated by the MSPA algorithm converges to i.e.,

Proof.

The proof is based on the construction of a sequence of points generated by Algorithm 1, which converges to a limit point that is the global minimizer of on . Let be the sampling sequence satisfying (9), (12), (13). Let us consider that for all the set of the elements of the sequence is then infinite and therefore has at least one limit point in Let be any limit point of such that then the convergence to is bilateral (one can see [12]). Consider the interval determined by (12) at the -th iteration. According (9) and (13), we have that the new point divides the interval into the subintervals and , so we can deduce

| (14) |

In addition, the value that corresponds to is given by

| (16) |

where is obtained by replacing by in (9). As and from (15) then we have

| (17) |

On the other hand, according to (11)

| (18) |

Since is the global minimizer of over

thus, we have

then

2.4. Estimating of unknown Hölder constant

The algorithm MSPA presented in the section 2 of this paper is applied to a class of Hölder continuous functions defined on the closed and bounded interval of when suppose a priori knowledge of the Hölder constant . However, the constant may be, in most situations, unknown and no procedure is available to obtain a guaranteed overestimate of it. Then, there is a need to find an approximate evaluation of a minimal value of . The algorithm we will extend does not require a priori knowledge of the . To over come this situation, a typical procedure is to look for an approximation of during the course of search ([11], [12], [21]). We consider a global estimate of , for each iteration. Let the sampling points and the values are also calculated. Let

and

Let be the multiplicative parameter as an input of the algorithm and be a small positive number. The global estimate of then is given by:

The condition , for all , indicates that the objective function is not constant over the feasible interval . Now from the definition of the global estimate , we replace in the formulas of and , the constant by also the point is replaced in the structure of the algorithm MSPA by the point where:

| (20) |

| (21) |

3. Multivariate Hölder global optimization

3.1. Reducing transformation procedure

Directly applying Piyavskii’s method to multivariate Hölder optimization is often impractical due to the computational cost of repeatedly minimizing the multivariate sub-estimator function [7, 20]. This sub-estimator is typically the upper envelope of many individual support functions (), and finding its minimum involves complex geometric operations (finding intersections of hypersurfaces).

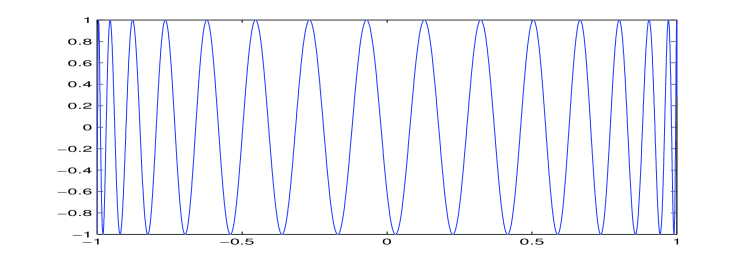

To circumvent this difficulty, we employ a dimension reduction strategy. Such approaches, often utilizing space-filling or -dense curves to map the -dimensional domain to a one-dimensional interval, have a history in global optimization, see, e.g., Butz [4], Strongin [18] and Ziadi et al. [9, 16, 22, 23]).

Our proposed multivariate algorithm combines a specific reducing transformation with the specialized univariate Hölder optimization algorithm MSPA developed in Section 2. The key idea is to define a parametric curve , where is the original search box, such that the curve is -dense in . This property guarantees that for any point , there exists a such that .

Definition 4.

Let be an interval of . We say that a parametrized curve of defined by is -dense in , if for all , such that

where stands for Euclidean distance in .

By restricting the objective function to this curve, we obtain a univariate function , defined by:

Crucially, if is Hölder continuous and is sufficiently regular (Lipschitz), the resulting function is also Hölder continuous on the interval . The original -dimensional problem (1) is thus effectively reduced to the one-dimensional problem:

| (P) |

This univariate problem can be efficiently solved using the algorithm from Section 2. The quality of the approximation to the original problem depends on the density parameter of the curve.

Theorem 5.

Let be a function defined from into . Let and denote the Lebesgue measure, such that:

-

(1)

are continuous and surjective.

-

(2)

are periodic with respective periods .

-

(3)

For any interval and for any , we have:

Then, for , the function is a parametrized -dense curve in . (The proof can be found in [24]).

Corollary 6.

Let a function defined by:

where are given strictly positive constants satisfying the relationships

Then the curve defined by the parametric curve is -dense in [24].

Remark 7.

According to Corollary 6, the parametrized curve is -dense in the box . Moreover, the function is Lipschitz on with constant:

Theorem 8.

The function for is a Hölder function with constant and exponent .

Proof.

For and in , we have

As the function of the parametric curve is Lipschitz on with the constants , we have

then

hence

∎

3.2. The Mixed RT-MSPA Method

For determine the global minimum of on the mixed RT-MSPA method consists of two steps: the reducing transformation step and the application of the MSPA algorithm to the function on .

3.3. Convergence Result of RT-MPSA

Theorem 9.

Let be a Hölder function satisfying the condition (2) over and be the global minimum of on . Then the mixed RT-MSPA algorithm converges to the global minimum with an accuracy at least equal to .

Proof.

Denote by the global minimum of on , where On the other hand, let us designate by the global minimum of the problem obtained by the mixed method RT-MSPA. Let us show that

-

1)

As is continuous on , there exists a point such that Moreover, there exists such that so that

And therefore

But from , we deduce that

(22) -

2)

As is continuous on there exists a point such that , involving as a global minimizer of . Then is a limit point of the sequence obtained by the mixed algorithm.

Hence and . i.e.,

On the other hand, since is the global minimum obtained after iterations, we obtain:

so that

Consequently,

(23)

Finally, from (22) and (23), the result of Theorem 9 is proved. ∎

4. Numerical experiments

This section details the numerical experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed MSPA algorithm against existing methods, specifically SPA [12] and TPA [5], [8]. Two series of standard test functions and their corresponding data are listed in Table 1 and Table 4. Most of them have different properties like non-convex, non-differentiable and have more than at least two local and global minima. The evaluation covers both single-variable and multivariate optimization problems.

For all single-variable experiments, the desired accuracy for locating the global minimum was set to , where is the search interval.

The primary performance criterion used for comparison are the total number of function evaluations () required and the CPU execution time in seconds (). Detailed results for the known and estimated Hölder constant are presented in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Within these tables, results shown in bold indicate the best performance achieved among the compared algorithms for each criterion ( and ) on a given test problem.

For multivariate optimization, we implemented the Reducing Transformation (RT) approach combined with the MSPA algorithm, utilizing -dense curves with a density parameter . Comparative results for The known and estimated Hölder constant are presented in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively.

The experiments were implemented in MATLAB and performed on a PC.

| Function | Interval | Hölder constant | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [21] | |||

| 2 | ||||

| [7] | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | [20] | |||

| 7 | [5] | |||

| 8 | [14] | |||

| 9 | [14] | |||

| 10 | ||||

| 11 | [14] | |||

| 12 | [14] | |||

| 13 | [14] | |||

| 14 | ||||

| 15 | ||||

| 16 | ||||

| 17 | ||||

| 18 | [15] | |||

| 19 | ||||

| 20 |

| Problem number | SPA | TPA | MSPA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 78 | 0.1167 | 74 | 0.0639 | 78 | 0.0655 |

| 2 | 2 | 2005 | 1.5050 | 2107 | 1.5976 | 2129 | 1.6245 |

| 3 | 2 | 4371 | 9.0077 | 2812 | 4.3383 | 3965 | 7.8945 |

| 4 | 2 | 254 | 0.1302 | 96 | 0.0711 | 104 | 0.0735 |

| 5 | 2 | 295 | 0.1940 | 79 | 0.0689 | 110 | 0.0957 |

| 6 | 2 | 3433 | 4.0167 | 3061 | 3.1928 | 3013 | 3.1567 |

| 7 | 2 | 4403 | 6.6673 | 4185 | 5.9728 | 4487 | 6.9423 |

| 8 | 3/2 | 87 | 0.0642 | 86 | 0.0636 | 89 | 0.0677 |

| 9 | 2 | 87 | 0.0657 | 86 | 0.0676 | 82 | 0.0650 |

| 10 | 2 | 704 | 0.2988 | 46 | 0.0653 | 696 | 0.2894 |

| 11 | 2 | 2867 | 2.8312 | 1721 | 1.1843 | 2149 | 1.6457 |

| 12 | 2 | 207 | 0.1419 | 216 | 0.0942 | 206 | 0.0905 |

| 13 | 2 | 1179 | 0.6164 | 1333 | 0.6984 | 1226 | 0.6143 |

| 14 | 2 | 2109 | 1.7937 | 1701 | 1.0748 | 1527 | 0.8923 |

| 15 | 2 | 3169 | 3.5469 | 3233 | 3.7415 | 3201 | 3.6079 |

| 16 | 2 | 2109 | 1.9788 | 1587 | 0.9685 | 1456 | 0.8341 |

| 17 | 3/2 | 668 | 0.6360 | 70 | 0.0637 | 697 | 0.2672 |

| 18 | 2 | 1342 | 0.7609 | 874 | 0.3612 | 864 | 0.3611 |

| 19 | 2 | 91 | 0.1198 | 83 | 0.0703 | 79 | 0.0688 |

| 20 | 2 | 2787 | 2.7692 | 1835 | 1.2205 | 1809 | 1.2010 |

| Problem number | SPAes | TPAes | MSPAes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 37 | 0.0116 | 48 | 0.0104 | 37 | 0.0064 |

| 2 | 2 | 1215 | 5.4778 | 962 | 3.5355 | 667 | 1.8018 |

| 3 | 2 | 2271 | 20.869 | 1819 | 13.717 | 1877 | 15.585 |

| 4 | 2 | 1288 | 6.4384 | 546 | 1.1884 | 240 | 0.2420 |

| 5 | 2 | 2854 | 31.324 | 575 | 1.2967 | 1104 | 4.8313 |

| 6 | 2 | 1501 | 8.6159 | 1841 | 12.972 | 1438 | 8.3665 |

| 7 | 2 | 1018 | 3.8064 | 1224 | 5.7721 | 1467 | 8.4715 |

| 8 | 3/2 | 22 | 0.0025 | 23 | 0.0026 | 21 | 0.0030 |

| 9 | 2 | 32 | 0.0049 | 31 | 0.0047 | 30 | 0.0044 |

| 10 | 2 | 986 | 3.7106 | 1062 | 4.3083 | 815 | 2.7356 |

| 11 | 2 | 1937 | 14.211 | 2446 | 22.842 | 2676 | 28.106 |

| 12 | 2 | 54 | 0.0126 | 69 | 0.0200 | 66 | 0.0194 |

| 13 | 2 | 1193 | 5.4486 | 914 | 3.2404 | 1364 | 7.3024 |

| 14 | 2 | 1391 | 7.3437 | 1707 | 11.168 | 1282 | 6.4865 |

| 15 | 2 | 1350 | 6.930 | 1540 | 9.0673 | 1045 | 4.3092 |

| 16 | 2 | 1995 | 15.269 | 1545 | 9.1268 | 1595 | 10.213 |

| 17 | 3/2 | 910 | 3.5283 | 638 | 1.7160 | 655 | 2.6685 |

| 18 | 2 | 578 | 1.2773 | 386 | 0.5728 | 437 | 0.7776 |

| 19 | 2 | 77 | 0.0246 | 74 | 0.0231 | 66 | 0.0191 |

| 20 | 2 | 687 | 1.7730 | 748 | 2.1631 | 553 | 1.2303 |

| Function | Box | Hölder constant | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [20] | |||

| 2 | [16] | |||

| 3 | [15] | |||

| 4 | [15] | |||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | 1 | [3] | ||

| 7 | [3] | |||

| 8 | [3] | |||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 | [3] | |||

| 11 | [16] | |||

| 12 | [16] | |||

| 13 | [16] | |||

| 14 | [16] | |||

| 15 |

| Problem number | RT-SPA | RT-TPA | RT-MSPA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 9131 | 28.642 | 8875 | 26.875 | 9055 | 28.103 |

| 2 | 2 | 1493 | 0.8627 | 1459 | 0.8278 | 1425 | 0.8030 |

| 3 | 3/2 | 6298 | 13.532 | 6255 | 13.316 | 6248 | 13.412 |

| 4 | 3/2 | 1053 | 0.4863 | 990 | 0.4411 | 986 | 0.4489 |

| 5 | 2 | 2844 | 2.8212 | 2770 | 2.6870 | 2692 | 2.600 |

| 6 | 2 | 218 | 0.0806 | 238 | 0.0868 | 213 | 0.0802 |

| 7 | 2 | 214 | 0.0769 | 196 | 0.0920 | 186 | 0.0734 |

| 8 | 2 | 331 | 0.1102 | 297 | 0.0997 | 319 | 0.1088 |

| 9 | 2 | 5795 | 11.432 | 5536 | 10.468 | 5507 | 10.501 |

| 10 | 2 | 4024 | 5.3531 | 4266 | 6.0112 | 3724 | 4.6304 |

| 11 | 2 | 2046 | 1.5416 | 2010 | 1.4863 | 1973 | 1.4524 |

| 12 | 2 | 509 | 0.1726 | 478 | 0.1615 | 475 | 0.1625 |

| 13 | 2 | 6309 | 13.646 | 6342 | 13.534 | 6257 | 13.335 |

| 14 | 2 | 6972 | 17.1265 | 6805 | 15.8143 | 6776 | 15.6564 |

| 15 | 2 | 497 | 0.1703 | 485 | 0.1682 | 480 | 0.1662 |

| Problem number | RT-SPAes | RT-TPAes | RT-MSPAes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2.1 | 2938 | 36.910 | 2460 | 26.040 | 2317 | 33.541 |

| 1.07 | 1194 | 6.0336 | / | / | 1147 | 8.2836 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 665 | 1.6772 | 614 | 1.4797 | 607 | 1.4337 |

| 1.07 | 435 | 0.7450 | / | / | 231 | 0.2266 | ||

| 3 | 3/2 | 1.5 | 636 | 1.7097 | 742 | 2.2662 | 732 | 3.2807 |

| 1.07 | 466 | 0.926 | / | / | 286 | 0.5239 | ||

| 4 | 3/2 | 1.5 | 276 | 0.3303 | 267 | 0.3049 | 296 | 0.5407 |

| 1.07 | 163 | 0.1200 | / | / | 136 | 0.1193 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1595 | 9.6273 | 1765 | 11.474 | 1711 | 11.357 |

| 1.07 | 1356 | 6.9890 | / | / | 1289 | 6.7921 | ||

| 6 | 2 | 3.1 | 610 | 1.4298 | 674 | 1.6995 | 591 | 1.3795 |

| 7 | 2 | 3.5 | / | / | 534 | 1.0745 | 506 | 1.0562 |

| 8 | 2 | 3.1 | 521 | 1.0367 | 1140 | 4.7631 | 529 | 1.1228 |

| 9 | 2 | 4.05 | 130 | 0.0697 | / | / | 33 | 0.0059 |

| 10 | 2 | 1.5 | 1723 | 11.188 | 2355 | 20.513 | 1966 | 15.084 |

| 1.07 | 1530 | 8.9580 | / | / | 965 | 3.8254 | ||

| 11 | 2 | 14.4 | 290 | 0.3300 | 310 | 0.3749 | 310 | 0.3992 |

| 12 | 2 | 3.1 | 472 | 0.8553 | 459 | 0.7910 | 472 | 0.8762 |

| 13 | 2 | 1.5 | 134 | 0.0739 | 147 | 0.0855 | 145 | 0.0873 |

| 1.07 | 79 | 0.02688 | / | / | 55 | 0.01473 | ||

| 14 | 2 | 1.5 | 2792 | 29.536 | 3134 | 36.0570 | 2923 | 32.761 |

| 15 | 2 | 1.5 | 84 | 0.0306 | 33 | 0.0055 | 53 | 0.0135 |

4.1. Discussions and remarks

The primary contributions of this paper are the development of MSPA, an enhanced version of Piyavskii’s algorithm for finding global minima of univariate Hölder continuous functions, and its extension, RT-MSPA, for solving higher-dimensional problems.

For the univariate problem, the comparison involves two cases based on the availability of the Hölder constant :

-

•

Known Hölder Constant (): The standard SPA, TPA, and MSPA algorithms were used directly. The results are presented in Table 2.

-

•

Unknown Hölder Constant (): Modified versions of the algorithms, employing an estimation procedure for the Hölder constant, were used. These are denoted as SPAes, TPAes and MSPAes, respectively. These versions utilize an estimate of the true Hölder constant . The first remark in Table 3 that the results are obtained with the same value of (multiplicative parameter) and (tolerance parameter).

In higher-dimensional problems, comparative results are also presented for two cases, based on the availability of the Hölder constant :

-

•

Known Hölder Constant (): The corresponding results are shown in Table 5 for the test problems listed in Table 4.

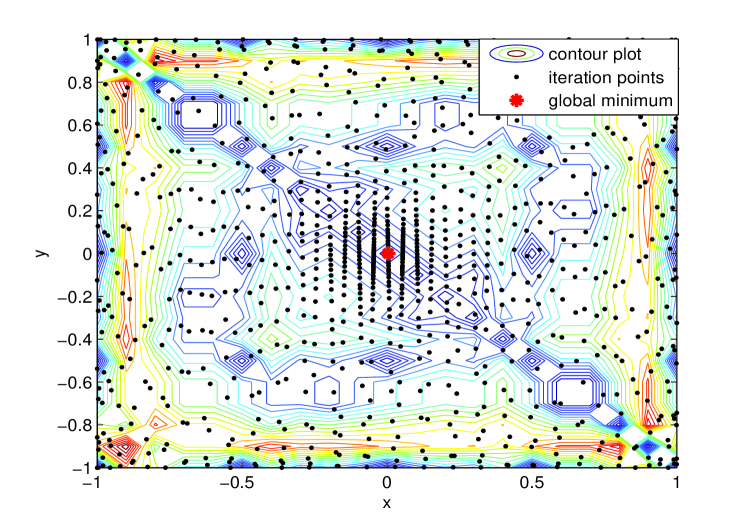

In this context, Fig. 3 provides a numerical example illustrating how the RT-MSPA algorithm converges, by showing the iteration points produced by this algorithm around the global minimum.

-

•

Unknown Hölder Constant (): Table 6 presents a comparison between RT-MSPAes and the corresponding estimation-based versions of existing algorithms (RT-SPAes and RT-TPAes), where is estimated.

Moreover, in this case with the estimation of , we observed that using and often yielded better results than . Notably, the RT-TPAes method failed to produce results when .

It should be noted that for the multivariate tests in Table 6 (unknown ), two different values for the parameter (typically and ) were generally used in the estimation procedure to obtain the reported results. The symbol (/) in Table 6 indicates instances where results could not be obtained for , particularly for the RT-TPAes method.

Indeed, the TPA method (known ) is often faster and requires fewer evaluations according to Table 2, when comparing with SPA and MSPA. However, even in this case, the performance of MSPA remains competitive when compared to TPA. A possible reason for this is that for certain functions with a known Hölder constant , the more aggressive linear approximation used by TPA is more effective at quickly locating the global minimum than the secant-based approximation of MSPA. This can be particularly true for functions where the Hölder exponent is close to 1, making the function’s behavior more linear.

In the case where is unknown a priori, the situation is different (see Table 3). Also, according to Table 5 and Table 6, in the cases where is known and is unknown, the performance of MSPAes and RT-MSPAes is more competitive compared to the other algorithms.

Finally, for problems with a known Hölder constant , MSPA required 68.42% fewer function evaluations than SPA, and 50% fewer than TPA. It also achieved an 80% reduction in execution time compared to SPA, and 50% compared to TPA. When the Hölder constant is unknown, MSPAes maintained strong performance, requiring 78.95% fewer evaluations than SPAes, and 60% fewer than TPAes, while also reducing execution time by 75% and 55%, respectively. Similarly, RT-MSPAes demonstrated its efficiency for problems with an unknown constant , achieving up to 61.9% fewer function evaluations than RT-SPAes, and 85.71% fewer than RT-TPAes, along with execution time reductions of 54.55% and 68.18%, respectively.

Based on these comparative studies, the MSPA, MSPAes, RT-MSPA, and RT-MSPAes algorithms demonstrate higher efficiency compared to the other techniques evaluated.

5. Conclusion

This paper addressed the global optimization of multivariate Hölderian functions defined on a box domain in . A key focus was the challenging yet practical case where the Hölder constant is unknown a priori. To tackle this class of problems, we developed and analyzed two novel algorithms: the MSPA and RT-MSPA. We provided rigorous mathematical proofs establishing the convergence guarantees for both proposed methods. To evaluate their practical efficacy, MSPA and RT-MSPA were implemented and tested on a suite of standard functions commonly used in global optimization literature. The numerical results were compared against those obtained by other well-known search methods. This comparative analysis demonstrated the viability and effectiveness of our approach, in particular, offers a competitive performance in practice. Future work could explore further adaptive strategies within the partitioning framework or extend the approach to handle different types of constraints.

Acknowledgements.

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referee for his useful comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the presentation of this paper.

References

- [1]

- [2]

-

[3]

N. K. Arutynova, A. M. Dulliev, V. I. Zabotin,

Algorithms for projecting a point into a level surface of a continuous function on a compact set,

Computational Mathematics and Mathematical Physics, 54 (9) (2014), pp. 1395–1401.

https://doi.org/10.1134/S0965542514090036

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [4] A. R. Butz, Space filling curves and mathematical programming, Information and Control, 12 (1968), pp. 314–330.

-

[5]

C. Chenouf, M. Rahal,

On Hölder global optimization method using piecewise affine bounding functions,

Numerical Algorithms, 94 (2023), pp. 905–935.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11075-023-01524-x

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [6] Yu. G. Evtushenko, Algorithm for finding the global extremum of a function (case of a non-uniforme mesh), USSR Comput, 11 (1971), pp. 1390–1403.

-

[7]

E. Gourdin, B. Jaumard, R. Ellaia,

Global optimization of Hölder functions,

Journal of Global Optimization, 8 (1996), pp. 323–348.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02403997

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [8] D. Guettal, C. Chenouf, M. Rahal, Global Optimization Method of Multivariate non-Lipschitz Functions Using Tangent Minorants, Nonlinear Dynamics and Systems Theory, 23 (2) (2023), pp. 183–194.

-

[9]

D. Guettal, A. Ziadi,

Reducing transformation and global optimization,

Applied Mathematics and Computation, 218 (2012), pp. 5848–5860.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2011.11.053

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[10]

P. Hanjoul, P. Hansen, D. Peeters, J. F. Thisse,

Uncapacitated plant location under alternative spatial price policies,

Management Science, 36 (1990), pp. 41–47.

https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.36.1.41

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [11] R. Horst, P. M. Pardalos, Handbook of Global Optimization, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, Dordrecht, London, 1995.

-

[12]

D. Lera, Ya. D. Sergeyev,

Global minimization algorithms for Hölder functions,

BIT Numerical Mathematics, 42 (2002), pp. 119–133.

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021926320198

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[13]

S. A. Piyavskii,

An algorithm for finding the absolute minimum for a function,

Theory of Optimal Solution, 2 (1967), pp. 13–24.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-5553(72)90115-2

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [14] M. Rahal, D. Guettal, Modified sequential covering algorithm for finding a global minimizer of non differentiable functions and applications, Gen, 22 (2014), pp. 100–115.

-

[15]

M. Rahal, A. Ziadi,

A new extension of Piyavskii’s method to Hölder functions of several variables,

Applied Mathematics and Computation, 197 (2008), pp. 478–488.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2007.07.067

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[16]

M. Rahal, A. Ziadi, R. Ellaia,

Generating -dense curves in non-convex sets to solve a class of non-smooth constrained global optimization,

Croatian Operational Research Review, (2019), pp. 289–314.

https://doi.org/10.17535/crorr.2019.0024

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[17]

B. O. Shubert,

A sequential method seeking the global maximum of a function,

SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 9 (1972), pp. 379–388.

https://doi.org/10.1137/0709036

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[18]

R. G. Strongin,

Algorithms for multi-extremal programming problems employing the set of joint space-filling curves,

Journal of Global Optimization, 2 (1992), pp. 357–378.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00122428

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

- [19] A. Törn, A. Zilinska, Global Optimization, Springer–Verlag, 1989.

-

[20]

A. Yahyaoui, H. Ammar,

Global optimization of multivariate Hölderian functions using overestimators,

Open Access Library Journal, 4 (2017), pp. 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1103511

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[21]

V. I. Zabotin, P. A. Chernyshevsky,

Extension of Strongin’s global optimization algorithm to a function continuous on a compact interval,

Computer Research and Modeling, 11 (2019), pp. 1111–1119.

https://doi.org/10.20537/2076-7633-2019-11-6-1111-1119

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[22]

A. Ziadi, Y. Cherruault,

Generation of -dense curves and application to global optimization,

Kybernetes, 29 (2000), pp. 71–82.

https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920010308871

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[23]

A. Ziadi, Y. Cherruault,

Generation of -dense curves in a cube of ,

Kybernetes, 27 (1998), pp. 416–425.

https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004524

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)

-

[24]

A. Ziadi, D. Guettal, Y. Cherruault,

Global Optimization: Alienor mixed method with Piyavskii–Shubert technique,

Kybernetes, 34 (2005), pp. 1049–1058.

https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920510605867

![[Uncaptioned image]](ext-link.png)